“Well, this is all bollocksed up,” I muttered to the burnt slice of bread peeking out from the silver top of the toaster. I stood in a pair of his clean knickers that I had nabbed from the laundry basket on his bed and a black tank top, puzzling over how to rid the smell of burnt toast from the apartment. It was almost alarming how comfortable, and moreover at home, I suddenly felt. Before I could make a move, I heard the lock turn and the door open. “Oh fuck, burnt toast. My favorite,” he said, coming into the kitchen and giving me a smile. “I know,” I replied, grimacing. “Sorry for the smell.” I walked over to the balcony door and gave it a pull; the glass slid open easily with a rumble along the track. “Are those my shorts?” he asked as I came back into the kitchen. “Erm, ya, sorry,” I said, shrugging awkwardly. He smiled, relaxed as always. “It’s ok. They look good on you.” He reached for a bag of what I knew was bakery contraband. “Thought we’d have a proper breakfast,” he said, bringing the bag to the table and fetching a few plates, knives, and miscellaneous breakfast elements from the fridge. “I thought you’d be in the studio by now,” I remarked, scooping coffee into the french press and setting the kettle to boil. “I was there already. I’ll need to go back.” He checked his watch. “I don’t have much time actually. I didn’t want to work on an empty stomach, though,” he added, winking at me. “Of course,” I replied as we sat down. “And I wanted to see you, of course,” he said, very seriously. I smiled and shrugged a shoulder. We had slept separately last night, but there had been an undeniable gravitational shift to pull us towards any surface we could get into a supine position upon. A lion’s heart had enabled us to resist. That, and the feeling that I would’ve been making love to a man who technically still belonged to the lingering energy of Lila.

I cleared my throat of bread crumbs, sipped a tangy bit of coffee, and wiped at the corners of my mouth. “So, I, uhm, well I’ve been in Berlin for awhile now, and I was thinking I should probably do another travel piece rather soon, and I was going to book a trip, four days I think, to Spain, Costa del Sol, and I thought perhaps, maybe, you’d like to join me?” I offered, reaching defensively for the butter knife and smearing a hefty glob onto the soft white bun. “You know we can go as friends or something,” I added, shaking my head, hoping to make the situation less forward. I had never asked a man to accompany me on a writing trip. Ever. The words sounded more foreign to me than the language I had produced them in. “Mira, I don’t look at you as a friend, and I suppose I never have,” he replied factually. He went on. “I’d very much like to have a holiday. I think I’ve been on two or three since the studio opened. I’ll need to speak with Lila to get this all—settled first, and then I’d be free to join you.” We let that bit about him speaking with Lila sink over us before he spoke again. “Are you sure you want company? I didn’t think you much liked travel companions when you are writing,” he said, a knowing gleam in his eye. Sometimes, I somehow forgot how well he did know me. “Aaahh, yea, that’s still true, but I thought, I dunno, it could be an interesting change,” I replied, laying my palms face up on the table. “Indeed,” he said, cutting into another roll. Indeed.

He departed without ceremony or display of affection. We were in a precarious state of limbo that demanded us respect both Lila and our newly rekindled emotions. A large part of me was wishing that he would come to Spain with me that very weekend, getting things straight with Lila so that we could finally figure ourselves out without that uncomfortable presence hanging about in the background. Another part of me, though, wished him to decline the trip, from which I would then never return, sending my regards via courier who would also collect the rest of my belongings from his apartment and send them on to London while I drowned my sorrow in Tinto de Veranos and the waves of the Atlantic all along the Spanish coast until I made it to the shores of the Mediterranean on the Costa de la Luz. “Oh fuck off,” I told myself, “Give him a chance.” “Its a fucking mistake,” the other side of reason argued. “You’re fast approaching middle age, and now is not the time to fling shit at the wall and see what sticks.” I closed my eyes against the late morning sun flooding the balcony, and tried to focus my attention on the emails I was sending to various editors and employers. Instead, I opened a new tab, punched in the URL of my blog and logged in. After several clicks, I hit ‘post’ on a raging impulse, and uploaded to the homepage was a selfie of Marius and I, taken that very morning on the very place where I was now sitting to bask in the summer sun. We’d see what my readers would think of that. God knew that what the readers wanted, they always ended up getting. One way or another.

Month: April 2017

Unfinished Business (Mira pt. 2)

And so it came that after nearly twelve years, I felt a calling to return to Berlin. God only knew why. I certainly hadn’t a clue. If the city had been bubbling with life when I had been there before, by now it was bursting at the seams. Prosperity and trendiness marked every corner and window front. The hum had grown louder, the personality of the city stronger.

I waited a few days before contacting him. Marius. Often on my mind but never on my lips, his name and his smile resonated with me since I left him on the platform all those years ago. I debated whether I should write him, but in the end, curiosity won out, and I wrote him a clipped, friendly email asking him if he was still in Berlin. Seeing the words of his response on the digital page a day later gave me just as much excitement as being back in this city. After choosing neutral ground on which to meet upon, I took a deep breath and submerged my head under the metaphorical waters of what I would come to know as unfinished business.

Not the bright-eyed young man I had known, but rather an established, well-kept forty-three year old man stood to greet me at a small table of a bustling restaurant. His eyes and smile, though, remained exactly as they had been. And our easy art of managing conversation made me feel as if it had been a few months, and not over ten years, since we had last had a proper chat.

“Marius?” A woman’s voice from behind. He turned to look and stood up.

“Hello darling.” He gave the woman a quick kiss and helped her out of her jacket. “This is Mira, the friend I was telling you about. Mira, this is Lila, my girlfriend,” he said proudly, looking from her to me and back. We shook hands and sat down. I hadn’t known what I should expect. I did know he had a girlfriend, yet her edgy, fashion-forward style threw me for a loop. Her thick blonde hair pouring over her shoulders and down her back, voluminous and straight, and her perfectly penetrating jewel-toned eyes made her attractiveness undeniable and almost uncanny. She was tall and thin and otherwise intelligent and remarkable and if I hadn’t already finished my first glass of wine, I may have even been a little intimidated by her.

But there we sat, we three. I wondered how much Lila knew about the origins of Marius and I, but in the end found it irrelevant; we were only heading forward in time, never going back.

The bristles on his face that composed the shadow of a beard were a mix of browns, blondes and grays. His hair, now a bit more clipped than it had been back then, was still dark, with the occasional strand of grey falling to light. My hair, on the other hand, had held back on the grey, the first appearing, or becoming noticed, during my three day mini-crisis. So far, it was just the one, hidden under a layer of curls on the back of my head. Proof that nothing stays the same—not even something as simple as hair color.

Feeling welcome by everything, I decided to stay in Berlin. Not having been there in ten years, I allowed myself to think that it was high time for something to be written about the city. Much older than I had been the first time, I found myself in a completely different place—both literally and figuratively. Mostly though, I spent my time with Marius and his colleagues, headphones clapped over my ears listening to the recordings they made, or practicing my rusty German in conversation with them. I would write a feature on them, I decided, and if the editors didn’t like it, I would publish it on my blog.

The neighborhood where the studio was located had become even trendier than it had been ten years ago. With shops, cafes, bistros, and hotels lining the one-way streets, it was a almost only accessible on foot or bicycle. I spent my days drinking coffee at a little blue table in a corner of my new favorite cafe, shopping at the boutiques, and dining with Marius and Lila almost every night.

“How long do you plan to stay in Berlin, Mira?” Lila asked me casually one evening over post-dinner gin and tonics.

“Until I become inspired or coerced to go somewhere else,” I replied, half-joking. She smiled.

“You know you don’t have to stay in a hotel. You can stay at my apartment if you like. It’s not nearly as luxurious, but I promise it’s clean,” Marius offered. I flicked my eyes quickly to Lila, who looked accepting enough.

“That’s a generous offer. Thanks very much,” I replied, smiling.

The next morning, I appeared on his doorstep toting my three bags. He opened the door wearing a pair of fitted grey jeans with a black t-shirt, hair still damp from a shower.

“Come in, come in,” he said, “welcome.” I smiled a thank-you and rolled my luggage over the threshold.

The apartment was an enormous upgrade from what we had shared back in the day. Two spacious and airy bedrooms with private bathrooms attached to each stretched out the length of either side of the open living room. The back wall of the living room was all glass, sliding open to the wide concrete balcony. Above the living room was a loft, his office, set up with a desk with recording equipment and a computer, a violin rested in one corner, a guitar next to it, and an electric keyboard stood against the wall across from the desk. The living room itself was dressed with a grey sofa, a love seat in front of the glass wall, and two matching chairs across from the love seat. In one corner was a a compact bar, and in the other was a baby grand piano. Luxurious was precisely the word to describe the place.

When Lila walked in two hours later, unbeknownst to us, we were sitting together at the piano; I was plinking, he was playing, and we were both singing, an open bottle of Chardonnay and two empty glasses on the table next to us. We both turned around upon hearing the sound of something large and heavy thudding onto the counter in the kitchen.

“Lila?” he called. She came out of the kitchen smiling.

“You guys sound great,” she said lightly, looking from him to me. “I see you’ve opened a nice white to start the day.” She disappeared and came back with a wine glass for herself. She filled the three. “Cheers to you and you,” she said, never taking her green eyes away from mine.

I had been in Berlin for almost four weeks, two weeks longer than I had stayed anywhere since I left Switzerland. I had a budding friendship with Lila, and found myself on a coffee date with her on a warm April Monday. She had asked me to do some shopping with her, and we had spent the morning under the soft lights of the boutiques, each of us toting three full bags by the time we seated ourselves outside a fairly empty cafe for refreshment. We had just finished talking about how she and Marius had met, and she was lighting a cigarette.

“He’s not been very affectionate lately,” she said, turning her head to the left, the cigarette smoke escaping casually from her lips. If I had been paying better attention, I would’ve seen her watching me from the corner of her eye. Instead, I shrugged.

“I dunno. I mean, as a friend, he’s usually a great big hug-giver,” I said, smiling smally into my half-drank coffee, and then at her. She took a calculated drag from her cigarette and stubbed it out in the small white ash tray between us on the table. I waited for her to speak; she looked as if she needed to say something. Instead, she averted her eyes from mine to look at the activity surrounding us on the outdoor terrace. Four o’clock: time for the cafes to fill up with people in search of a nice piece of cake and a coffee to accompany it. This cafe was no exception. I joined her in people-watching, oblivious to her observations of me.

“He’s been different, you know.” Her voice startled me. “Since you got here,” she said. Then, I felt her green eyes boring into my cheek.

“What do you mean,” I asked, cupping my cooled off coffee mug. She was silent, still staring at me.

“He’s in love with you.”

I said nothing but I felt my brows crease together. She huffed a breath of air out through her nose. I noticed my hands, warm and moist against the cool ceramic of the mug. Then I began to shake my head.

“That’s not—really, it’s not like that. He and I, I mean, it was a long time ago, we don’t—he’s not, in love, with me, anymore. We’re just fr—“

“Don’t,” she said, raising her hands, palms facing me. She lowered them slowly, as if she meant to push away the earth beneath us. “Don’t,” she said again firmly, coldly.

I was still shaking my head, frantically almost.

“I knew it, from the first moment I joined you at the restaurant that first evening. I felt like,” she waved her hand and rolled her eyes, “like I was the third wheel, like I had joined an exclusive party of two,” she finished. She rummaged in her purse. As she looked down, her blonde hair fell like a curtain between me and her face.

“I, I don’t know why you think that, really. We, we haven’t seen each other in such a long time,” I reasoned, trying to keep the rock slide from turning into a crushing avalanche.

She made a sound in her throat as she began sprinkling tobacco onto a small paper.

“I hate you for it, you know. Not you as a person, really. But the idea of you. That you could come here after all these years and he just—,” she shrugged, “forgets that there was ever another woman in his life,” she said, rolling the paper carefully shut, bringing it to her lips to be sealed. As she lit the end, I tried to think of something, anything, to say in my defense. I was speechless.

“I don’t think it’s any fault of my own, though,” she went on. “I just, well, it fucking still feels like a betrayal. From both of you,” she said, taking a deep drag and pushing it right back out.

“Lila, I—“ My speech faltered as she pushed angrily back from the table. She stood up quickly, slinging her bag over her shoulder.

“No, Mira, you don’t get to say anything.” She stubbed the cigarette out aggressively and straightened up. “I just need you to fuck off right now, ok? I like you, really, I do. But, just, fuck off.” On that note, she turned from me and walked to where her bike was chained to a light post a few meters away from the cafe’s terrace. She slid a pair of dark sunglasses onto her face, mounted the cycle, and rode away without a backward glance in my direction.

My coffee was empty and I was alone. I flagged the waitress down and asked for a glass of wine, please. While all the others drank their caffeinated hot beverages and over-indulged in sweets, I finished off my glass of wine before asking for the bottle.

Luckily, I had the good sense to cork it and take it with me while it was still a third full. But where was I to go? Back to Marius’s? He and Lila did not live together, but she still might be there, insisting that he throw me out to go back to the boutique hotel I had crawled out of. I decided I would leave, but first I would have to get my belongings.

I arrived back at his building after moseying through the alleys, taking the long way, occasionally taking a pull from the bottle of wine stashed in my bag. My shopping bags bumped against my legs, threatening to trip me and send me on a trajectory that would end in a meet-cute with the ground. I pulled the key from my pocket and let myself in to the hallway before taking the lift up to his floor. I tried to be as inconspicuous as I could when I came in, muffling the sound of the door closing with my body.

“Mira? Is that you?” he called, coming around the corner from the kitchen. Something smelled really good. He was smiling at me. “Did you have a good day? It looks to have been productive,” he said, gesturing to the bags. I remembered to breathe, and then smiled at him.

“It was good, thanks,” I said politely, walking past him to head towards the guest room.

“I’m just preparing dinner. I hope you’re hungry,” he said to my retreating form.

“Let me just, erm, freshen up, and I’ll be out in a jiff,” I replied. I shut the wooden door behind me and found myself in the welcome silence of the sleek bedroom. Before I even realized what I was doing, the clothes were stuffed and rumpled in my suitcase, and I was gathering everything I had in the bathroom and funneling it into a cosmetic bag. I straightened up and glanced at my reflection. “Get a hold of yourself Mira,” it muttered to me. It was right; if nothing else, I had to say a proper good-bye to Marius. I quickly changed my clothes and tentatively stepped out into the living room. He was putting on a record, a bottle of wine stood next to an empty glass. He turned around, bearing a full wine glass and a smile.

I took a deep breath and went for it. No point tiptoeing around it. “Marius, I’m not really sure how to, well, I just had this rather startling conversation with Lila, actually. And she, well, she said that she believes that you, that you, well-oh fuck it, that you’re in love with me,” I said at last. His eyes dropped to the floor.

“I know what she thinks,” he said to the wooden paneling of the floorboards. “She’s been telling me since you arrived in Berlin.”

“And what did you say?” I asked very quietly, feeling a mounting discomfort that I had not ever known before.

“I told her she was out of her mind and left it that,” he said, shrugging. “But you know,” he continued, looking up from the floor and into my eyes, “that Lila is a self-assured woman with exceptional intuition. That’s what attracted me to her initially. And so, after awhile, I realized that she was right.”

My stomach dropped. He poured wine into the second glass and handed it over the space between us. I took it with a gulp.

“Why don’t we eat some dinner? None of this can be solved on an empty stomach,” he suggested, leading me gently toward the kitchen, toward the something that he had cooked for us. For us. Bloody fucking hell. There hadn’t been an “us” in over ten years. I grabbed his arm rather suddenly and he looked back at me in surprise. I let go immediately. “Eh, sorry, I just—do you think we could have a cigarette first?” I asked, wiping my suddenly moist palms on the thin fabric of the dress I had changed into. He smiled and gestured toward the wall of windows, the balcony an open-air piece of relief behind it.

My hands shook as I tried to gently perform the art of creating a hand-rolled cigarette. I knew he was watching me in his nonchalant, unbothered way. Finally, he gently took the crumpled, gossamer rolling paper from me and began crafting me a perfectly executed version, which he handed to me and pulled the lighter from his pocket to offer me use of its flame. I puffed deeply, coughing several times, looking away in embarrassment. For fuck’s sake.

We smoked in silence, watching the Berlin sun drop away to be borrowed by another part of the world. It was still warm, but my arms prickled into gooseflesh every time the gentle wind whispered past. He stubbed the end of his cigarette into one of the flower pots housing robust blooms. I watched him with a calculated amount of reserve, feeling painfully self-conscious while alone in his presence. I thought of the parts of him beneath his clothing I had seen, almost memorized, those years ago and found myself blushing profusely. “Jesus fucking Christ,” I muttered, casting the butt of my cigarette into the same pot. He pushed the door open and we went back indoors. I moved into my bedroom to find a shawl to drape around my shoulders, and when I came back, he was back in the kitchen removing a large pot from the stove. I hoisted myself silently onto a stool and waited patiently for the meal. Instead of offering my help, I poured a generous amount of wine into both of our glasses.

The only sounds were that of cooking and the plating of food, and the swallows of wine slipping down my throat which only I could hear.

While I had been alternating between staring at the dwindling contents of my wine glass and at the fresh manicure I had given myself that morning before shopping, Marius had been laying the table with beautiful things. “Do you want to come and sit down?” he asked me, a certain amount of hope in his eyes. I slid, somewhat unsteadily, from the stool and, clutching my glass, made my way to the place he had set for me across from his at the dining table. The fixture over the table was turned to dim, a handful of tapered candles took over the job of providing light. There was a mass of wildflowers in a vase, and a basket of freshly baked bread beside it. There was a platter of cheese, and a colorful green salad alongside it. The round white plates were artfully arranged with sautéed greens, roasted carrots, asparagus and potatoes, and there was a lush looking cut of beef glazed in a succulent sauce. “I meant to serve in courses, but I thought the meat might overcook,” he explained, gesturing to the elaborate spread. We sat down and he poured me more wine. We ate in silence until I ventured a compliment. “This is delicious. You’ve become an excellent cook. I hope you didn’t do all of this just for me,” I said, smiling. He smiled back. “Actually, I didn’t. I thought Lila would be joining us as well and we would have dinner altogether, but I gather she is otherwise indisposed,” he replied. I focused on cutting my meat, which took very little effort, and said nothing. “Mira,” he said, making me look up from my fascinating plate. He smiled smally. “Cheers.” I wiped my mouth. “Cheers,” I said, raising my glass. They came together with a delicate clink and then were drawn to our lips to have their contents ravaged.

At some point or another, normal speech resumed, and we put a form of temporary amnesia into place in order to avoid the elephant lurking, stomping about, just outside the dining room. As the wine warmed my body and I laid the shawl over back of my chair, I felt my soul warming as well. Warming to what, I could not say exactly. But I knew it was happening. Somewhere, some great mechanism was turning, creaking back to life, bringing us together again. Most importantly, I knew Lila was right; either he loved me very much, or was in love with me. The difference hardly mattered. I was not here to trifle with technicalities. No, I knew why I was here, and it had everything to with what his eyes were saying to mine, and how the now comfortable moments of silence said what words could not.

Unfinished Business (Mira: pt. 1)

It was the longest travel day of my life: Sydney to California, California to New York, New York to Berlin. Over thirty hours of flight time, not including layovers. My flight out of New York was delayed due to the rains that had been drowning the state for days, and I sat in the airport, a half a step from brain dead, not knowing what time it was or what day it might be. My fellow delayees and I did our best to sprawl out and make ourselves comfortable at the gate, and by the time a message from the loudspeaker that we would begin boarding in an hour had awoken me, I had gotten a reasonable amount of sleep and no longer felt like dog shit thrown into the bin. I straightened my clothes and headed for the bathroom, wiping at my smudged eyes as I looked at my sleepy reflection in the mirror.

Whenever I felt too hassled or troubled by traveling, I remembered that I had the job most twenty-six year olds would commit murder for. As a writer working for a prestigious travel magazine, I had been given the world on a platter, so to speak. I was paid to galavant across Europe, put up in the best hotels, and supplied with lists of the best places to shop and dine. I kept a small apartment in London, but rarely ever saw its interior. And currently, I was on my way back from a corporate trip in Sydney, Australia, where we staff had been treated to Sydney nightlife, Adelaide wilderness, and Victoria’s beaches. And I hadn’t paid a thing for it. Berlin was my next assignment; a city in Germany that I had not yet explored.

As always when it was time to board, it was also the time to put my thoughts away and get settled in for the next seven hours.

It is a known fact that crying children are never truly welcome on an airplane. Neither are men who insist on sitting with their legs spread wide apart, or individuals who have been too liberal with their fragrance. Unluckily, I was seated in the middle row of the plane, between a mother with a crying toddler and a man doused in cologne. I wondered very briefly if my boss would take pity on me and upgrade me to Business Class if I called and asked him very nicely. Instead, the presumed father of the unhappy child, a trendy New Yorker by the looks of him, leaned across the aisle and asked me if I wouldn’t mind trading seats with him. I glanced over to his row of three seats; sure enough, the guy at the window was slouched, knees apart, with a bowler hat over his face, taking up precisely one and a half seats worth of legroom. Luckily, the middle seat was open. I agreed to the exchange, and arduously moved myself and my belongings to the new location. My seat mate did not stir, and I busied myself with arranging my book, magazines, and tablet in the seat pocket in front of me.

It wasn’t until several hours into the flight that the man stirred, straightened his posture, and pulled the bowler hat off of his face. He stretched a little, looked out the window, and noticed me. “Oh, you’re not the guy that was sitting here before,” he said smiling, nonplussed.

“No, he opted to be next to his family,” I replied, looking up from my reading.

“Have we been flying long?” he asked, peering out the window as if he may get an answer from the blackness.

“About three hours, I think,” I replied, turning the page of my book.

“You’re reading; sorry, I didn’t mean to disturb you.” Something in his smile, though, made me want to smile back. And I did.

“No bother,” I said. “Going home?” I asked, somewhat presumptuously.

He nodded. “Yea. Well, Berlin isn’t technically where I’m from, but it’s home for now,” he replied. I nodded, and not knowing what else to say, went back to my book, only pretending to read. He was handsome; nice blue eyes, dark hair, good style…..

“Have you been there before?” he asked. I shook my head. “Nope, this is my first time,” I said, closing my book for good. I was ready to pursue conversation. He seemed like he might have an interesting thing or two to say.

“You’ll like it. It’s a great city. There’s a lot going on. Do you know where you’re staying?”

“Eh, yea, a pace called Das Stue,” I said, rather conscious of my shitty pronunciation.

“Hm, I don’t know that one, but I’m also not very familiar with the hotels in Berlin,” he said, smiling again. “Are you on holiday?”

“No, actually. I write for a travel magazine and Berlin is my next city of discovery,” I said, smiling. It always felt good to answer that question.

“What a great job. You’ll have a ton to write about. Berlin doesn’t disappoint,” he remarked.

“What about you? What do you do?”

“Well, I often ask myself that same question.” He smiled again. “What I’m trying to do is finish my Uni degree in Film Studies, and simultan—, simulta—fuck, what’s the word? Si-mal-tane-e-us-ly, trying to open a studio where I can record film music.” He shook his head.

“That’s really interesting. Is it working out?” I asked.

“It is. Slowly, but it is.”

I smiled. “That’s great.”

We talked. For the rest of the flight, the four hours remaining, we made conversation about you name it. Just as the final ‘beep’ went off to initiate the clicking of all passenger’s seat belts, he said, “I don’t know how weird this is, but if you ever need someone to, you know, take you around the parts of Berlin that not everyone knows of, I would be happy to do it.”

I smiled, squeezed my eyes shut briefly and thanked the gods, before turning to him.

“I think that would be very helpful indeed, can you give me your number?”

And from then on, it was game on.

I spent half of my nights in Berlin in that swanky boutique hotel. The other half, I spent in his one-bedroom apartment located in an up-and-coming neighborhood. He took me out, showed me the sights, brought me to his studio, played me music, and made love to me. Believe it or not, this was not typical of me. Very rarely did I ever make anything past a superficial connection with a man while traveling, and certainly never slept with the ones who bought me drinks.

It was three years, two of which were actually the embodiment of unparalleled happiness, before we finally decided we had to go our separate ways. We had begun to slip into a mutual understanding, a mere friendship that transferred us into the roles of roommates who occasionally slept with each other. When it came to the heart of things, we were both artists; artists who both had careers that had taken flight and recently begun soaring. I was approaching thirty with gusto, never slowing down, not even for a moment. How could I? My writing had, thanks to social media, gone global. I was freelancing and contracting as a stay-on for not only travel magazines, but also fashion and lifestyle publications. In addition, I was glued to my tablet or mobile phone, constantly tweeting or posting about something when I was wasn’t updating my blog, which was making me enough money to live on by then. For his part, he was working long hours, composing, going to meetings, and networking. He had already gotten his foot in the door of the German film industry and had begun reaching companies well outside of Berlin and even Europe. Between his twelve hour days and my erratic travel schedule, we saw next to nothing of each other outside of video chats where we gobbled down some take-away food and talked about the weather.

My mother, every time we would speak on the phone and no matter how briefly, would insist that we were going to start arguing if we didn’t spend more time together, and inevitably one of us would become bitter. As a result, I called her five minutes before I was due to board a flight so as to have a savvy excuse for not being able to listen to her full lecture. In all fairness to my mother, though, she loved him, and he her, and she wanted me to settle down a bit more since I was getting, as she so kindly put it, ‘older’.

On a cold and blustery Fall day, he brought me to the train station where I would catch the nine o’clock train to Geneva and from there, go on to the city of Montreaux. We were both running late and had not much time for a proper adieu. We stood together on the platform, hands clasped, a single tear rolled down my cheek as I watched his eyes well up. He brushed the water away hurriedly with a knuckle. “I’ll call you when I arrive,” I said, trying to smile, trying not to think of the stack of boxes in the foyer of our shared apartment that would be shipped to my flat in London the next day. “Have a nice trip,” he replied, smiling ever so smally.

“I’ll miss you.”

We kissed for a moment, looking and feeling like lovers, but we knew we were saying our last goodbye.

A whole decade passed in which we had little more contact than the occasional and very impersonal social media blip. Ten years is a long time for life to work in its mysterious ways, and the decade went by in a flash. I took up residence in a beautiful, sunlit apartment in a pre-war building standing on the banks of Lake Geneva in the Swiss city of Montreaux, home of a world-renowned jazz festival, and the exact city to which I had traveled when I left Berlin for the last time. I was not residing alone; in fact, I had met a Swiss man who had given me what had remained for me to desire from the world, including the recognition and acceptance of my occasional cultivated bi-sexual preferences. He was in his fifties and aging very well; a banker with a surprisingly docile demeanor. He was also divorced, on friendly terms with his ex, and childless. He liked me for my creative mind and wanderlust tendencies, and I liked him for his good taste and ever-present patience. Together, we made up a team of steadfast comfort and understanding. He was the type to take me on tours of his friend’s vineyards in the mountains, book a spontaneous long weekend for shopping in Paris, meet me for dinner when I was in London, and allow me to treat him to a stay in some fashionable London hotel. I never took him back to my flat because that had become the place of my very own, housing the part of me that never wanted to share, give up, or compromise anything.

Moreover, Montreaux was a stay in paradise. Beautiful during every season, the lake greeted me every morning from outside the bedroom balcony. For three quarters of the year’s days, the light colored wooden floors became silent underfoot, and the spacious living room became a basin of light all day long. Working from home became much more appealing. So appealing, in fact, that I began to leave Switzerland less and less. Instead, I took train trips to Bern, Lucerne, Interlaken, Geneva, or other cities, and occasionally, I would venture over the border into France. Actually, most of the international travel was done in the company of my dear partner. We breakfasted every morning together; he read the paper, while I exercised my fingers scrolling through emails and other alerts. He would head off to work, while I would place myself at the seat of my desk and begin to write something for someone, somewhere, but had mostly turned to blogging full-time.

One magnificently brilliant summer day as I leaned over the railing of the balcony, taking in the panoramic view that I had grown so accustomed too, I realized that I had grown incredibly established in my habits. There was no spontaneity to my day, and weeks went by in a similar fashion and structure. I wondered briefly if that made me happy or morosely depressed. Instead of answering myself, I frowned deeply and went back inside.

That very evening, over freshwater oysters, I broke the news of my discovery very delicately to my companion. I don’t think he was surprised; yet, I did note the sadness in his eyes when he looked up from buttering his bread after I told him I would be leaving. Truthfully, I was sad, too.

The next morning, I embraced him in the foyer one last time before he saw me to the door. While the doorman loaded himself up with my luggage, I took one last look behind me to see him standing there, hands in his pockets, sad smile on his lips, and the balcony doors thrown open to the breeze, the glistening lake winking behind him.

Opening the door to my flat in London, I couldn’t help but wonder if it had been a monstrous mistake to leave Switzerland. I looked around at the coffee table, sofa, and bookshelves, all dusty from months of disuse. I unpacked my things, straightened up, and, all the while tried to sort out the consequences of my actions. For three days, I hid from the world, keeping myself within the confines of my bed, crying over ridiculous movies and devouring tea sandwiches. By the time I knocked a bit of sense back into myself, my friends, family, and followers had all dropped me some kind of line, each sounding more concerned than the one before it.

And that was the end of my self-doubt and regret. I stayed no more than two nights in England before jetting off to the south of Italy, meeting up with friends and making new ones along the way. That first dive into the clear chartreuse waters of the Mediterranean gave me credence and clarity like nothing else could. This was where I was meant to be, and tomorrow it would be somewhere else. The rolling stone had not yet turned into sand.

The Last Ship (pt. 4)

The first time I saw pepsi being poured into the same glass as red wine, I thought to myself that some religious sacrament must have been obliterated. What’s more, it was done by Leo’s grandfather, Francessco, affectionately called Nono Cico by his grand- and great grandchildren. As the wine aficionado of the family, he had been responsible for running the vineyards and producing the wine for the last five plus decades. Now, he was a weathered and wrinkled old Italian man, who was missing a few teeth and walked with a stoop in his back. For a patriarch, though, he was mild-mannered and soft spoken. In fact, he spent most of the lunches eating the smallest portion he could get away with without the women making a fuss, and filling his glass over and over, half-half, with the red wine and cola mix. Like the shrimp with their long antennae, bodies still intact, googly eyes staring up from the plate as they lay on their bed of pasta, I surmised it must be an acquired taste. One day, he caught me staring and grinned sheepishly at me. He offered me the bottle of cola, which I turned down with a polite smile and slight shake of the head, and he set it down next to his chair before tucking his hands into his armpits, smiling at me again briefly, and turning his head to listen to an anecdote his daughter-in-law was brazenly telling to the world. I still had not grown accustomed to the boisterous expression that every conversation was required to be spoken in. But at least I had stopped wincing every time the person next to me decided to join in.

On a hot July day, at the peak of tourist season, I found Leo’s sister, Elisa, skulking in the shade on the steps that lead down to our apartment. I had been hurriedly on my way to scavenge whatever would be left and sold cheaply at the market, but stopped in my tracks when I saw the tear stains on her cheeks.

“Elisa? Are you alright?” I asked her tentatively. We had spent a few evenings cooking together and watching television after Leo came home from work, but I still didn’t know quite where I stood with her.

I had ventured my question in Italian, but she responded in English. She shrugged and rolled her eyes. “Fine. Just another stupid fight with my stupid boyfriend.” Taking a closer look, she looked more angry than sad.

“Oh. I’m sorry to hear that,” I began, trying my best not to act awkwardly. “Would you…like to talk to me about it? Or anything else…” I said, my eyes darting to hers and then away again. She stood up, surprising me.

“That would be nice. Let’s get a bottle of wine from the fridge. It’s hot as hell, and I’m in crisis.”

For the first part of the conversation, we sat in the cool dark of the apartment. We drank, and she told me the premise of the argument in perfect English. “He was supposed to come down here this weekend. He has a car, and he can take holiday from work. Because that’s what all people do in Rome in summer—they get the hell out of there. It’s oppressive, you see.”

What I saw was a beautiful, dark-skinned young woman who probably could have any man in this town, Rome, or Europe if she wanted to.

“Anyway, he decided he is going north, to Milan, to visit his sister and brother.” She raised an eyebrow at me and drank, draining her glass and refilling it. “He drives me completely crazy because he never does what he says he will. Its always about his fucking wishes, and he never seems to consider my feelings. What about what I want?” She was looking at me, and I didn’t know if I should answer, so I just nodded my head. “All my life people have been telling me what to do, where to go, how I should look, what I can wear, blah blah blah. I’m sick of it. Fuck them. Fuck him. For once, I would like to make the decisions.” She stood up. “Come on, I’ll show a place to sit outside. I need a cigarette and more wine.”

I followed her out onto the terrace where she led to me to a shady corner. She climbed onto the low wall, and there we sat. She lit a cigarette.

“Don’t take this wrong way,” I began as she poured us more wine, the cigarette pressed between her lips, “But your family is really intense.”

At this she laughed. “You have no idea.” Her brown eyes met mine. She pulled the cigarette away from her mouth and exhaled. “Then again, you probably do. I can only imagine how we look to you.” Again, she rolled her eyes.

I shrugged. “I’m struggling to fit in, that’s the problem really,” I said.

“Don’t try to fit in,” she said. I looked up at her. She waved a hand. “Not worth it. They’ll take everything you are. If you give them something, they’ll shape you into what they want, not who you want to be.”

“Well, there can’t be much to be done with me, I don’t even really know the language.”

“Good, that’s better. Believe me. And when you do, fake that you don’t.” She drew on her cigarette again. “For the past three summers, I haven’t come back here. Now I remember why.”

“Where did you go? Did you stay in Rome?” I asked.

She shook her head. “No, that would never do. The first summer, I went with a friend to Switzerland and worked in an expensive hotel in Geneva. After that, things became a little more complicated.” She was smirking. “Its really nothing I should be proud of, but it was my best act of rebellion.”

“What happened?” I asked, thoroughly intrigued.

She blew out the last cloud of smoke and stubbed out the cigarette on the cracked tile next to her. “Well, the first thing you need to know is that I’ve always wanted to be an actress. Not like Hollywood or any bullshit like that. Like a theater actress, maybe even an opera singer, though I think it may be a little too late for that. Anyway, my parents, they said that would never do. ‘Actors everywhere are starving and can’t pay their rent’, that’s what they said. A doctor is a respectable profession, and I could come back home and open a practice and take care of all my ailing relatives as they aged.” She shook her head. “That’s fine, if you’re not me. I couldn’t accept this life without putting up a little fight.”

“But aren’t you studying medicine in Rome?” I asked.

She nodded. “Yes, but gynecology. Not general medicine. That is rebellion number one.” She smiled proudly, and I raised my glass to her.

“So, because I was determined to pursue my dream on top of my university studies, I decided to go abroad to make money during tourist season. It started in Switzerland at the hotel, and from there it was France, where I was a cocktail waitress who sold expensive liquor and good cocaine to wealthy men and women who weren’t their wives.” She stopped, waiting for me to react. I kept my face smooth, and she continued. “After that, I spent a summer in Berlin, working for a nightclub. Some nights I bartended, some nights I was a dancer, whatever they needed. I kept the patrons who knew about it supplied with coke, and had sex with more djs than I can remember.” She laughed. “But the money was amazing. And I finally had enough to start taking acting lessons in the evenings when I didn’t have classes. I booked my first gig last fall, and since then, I have been doing small productions here and there, and now I take singing lessons, too.”

“And your parents don’t know?”

“They don’t know a thing. They would of course die if they did. But, I know my mind, and I will always fight for my happiness.”

I nodded, wondering how that must feel. She reached for the package of cigarettes. “Hmm?” she asked, gesturing to me with it. I took one and she held the flame out, lighting the end. We sat in the quiet heat and smoked, a sense of peace in the still and heavy air.

“Your English is perfect, Elisa. I had no idea,” I said after awhile.

She laughed. “Yes, I took English lessons, too. But I can’t let them know that, can I.”

I felt myself smile.

“Does Leo know?”

“Leo knows everything. But Leo knows his own mind, too. He got out of here, too. At least for a time.” She ashed in the brush.

What do you think will happen now that he’s back?” I asked, half-fearful of the answer she might give.

“Nothing. What can happen? He will take over the wine, as is his duty. He will pretend like my mother is in charge, but he pulls the strings really. He’s much smarter than they are. And plus, he has you.”

“What do mean?”

“You’re the woman of his life, Lillya. He would do anything for you now, because you did everything for him.”

I was quiet, letting her words sink over me.

She continued. “He is worried that you do not know what you want. But I think you do. You just have to, you know, bring it to the surface somehow. You are smart. And beautiful. You’ll do it.” She squeezed my arm and smiled.

We finished our cigarettes and the second bottle of wine. By the time it was empty and lying on its side, we were both giggling and talking absolute nonsense.

“Let’s go down to the sea. We can jump in naked and give all the old men a heart attack,” she said, giggling. Instead, we stumbled into the house and I went to the chest of mahogony drawers to fetch two swimsuits. She shamelessly shimmied out of her sheer sundress and out of her gossamer undergarments. I averted my eyes, afraid that she would catch me looking at her shapely body. I tried not to compare myself to her. However, the top of my suit did just enough to cover her breasts, which were at least two sizes bigger than mine. She laughed again. “This looks like what I wore in those German clubs,” she remarked.

A bit more modestly, I changed into my suit, and we left.

The Last Ship (pt. 3)

All my life I have been searching; searching for that spark, that intrinsic motivation that drives me, compels me to be. Through the years, its never been a what or a something that has moved me, it has always been a who. One night, after we had been sampling the previous year’s selection of reds, Leo pointed this out to me. “You have to know it somewhere inside of you, Lille. There is a qua within you that makes it happen. Maybe you just need to discover it; search yourself until you find it, and when you do, never let it go.” I sipped the wine carefully and tucked his words away in some foreground of my mind. I didn’t know what to say. He was right, he knew he was right. I knew it too, and therefore, there was nothing left to say about it.

I sat by the seaside the next day, watching the waves toss themselves over the pebbles of the rocky shore and felt more like one of those stones being washed about and dragged back and forth rather than the steadfast waves guiding the direction of it all. I squinted my eyes to look past what was directly before me in order to see the afternoon yachters mooring off to the side of the cliffs in the distance. I wondered what it would be like to be an anchor; to know your path and hold fast to it. The anchors would root down into the sand or the boulders of the sea floor and wouldn’t budge until they were pulled up and away, compelled to sail along to a new destination.

I pealed off the gossamer sundress that Leo had bought me the previous week and, in my bra and underwear, stood up from the comforting heat of the grey rock to wade into the warm embrace of the Mediterranean. I lay on my back as the water lapped over my stomach and legs. Arms outstretched, hair floating in all directions away from me, I thought, “I am the last ship; without moorings and without a course to lead me to a destination. What am I going to do?” Folding my body in half, I sank down until my lower back met the sandy bottom with a gentle bump. My fingers dug into the sand and pebbles and I tried to hold on as the bubbles escaped from my lips and nose. It was useless, of course; for the sand slipped through my fingers, and the pebbles were not enough to keep me down. Moments later, I floated to the surface, blinking away the sunlight and saltwater.

The dress clung to the water droplets that slipped down my body as I walked up the path back to the city. Moments later, they would be an effervescent memory. There was nobody around, of course; everyone in their right mind was sleeping the afternoon away, following the prescribed norms of southern Italian culture. Not me. I was the fish out of water.

When I came back to the house, Sonia, Leo’s mother, was sleeping on the white couch where I usually did my afternoon reading. Her mouth was slightly agape, one hand rested behind her head, and the other was laid over her minimally round, middle-aged stomach. It was amazing to me just how peaceful she looked when her matriarchal prowess was tucked away into the sub-conscious. Just hours before, she had been commanding me around the kitchen in her usual mix of Italian and English. She had become flustered because I didn’t understand that she wanted me to serve the mozzarella in the clear glass bowl rather than the usual green one. Her English abilities had failed her, and she had just shaken her head at me, voicing her displeasure in fluent Italian. Leo had tried to gently chide her, also in Italian, because he knew that those moments were ones of excrutiating embarassment for me. She had turned to him, gesturing to me with her ever moving hands, demanding some answer that he had not been able to give her. He had simply raised his hands in surrender, shook his head, and exited the kitchen. And I took the salad and the mozzarella in its correct bowl and had slipped silently from the room. His father, already seated at the table reading a novel, smiled up at me and squeezed my arm gently. Damiano knew what ailed me. He never said a word, but his eyes were always kind and empathetic, and I had to turn away to keep from tearing up in front of him. I also knew that he never spoke to his son about anything other than the business, family, and how to produce your greatest life’s work.

That night, when Leo came in from the vineyards, I was sitting at the table, a book open before me, and a half-eaten sandwich lay abandoned on the plate to my right. He was singing, so it must have been a productive day. He popped his head around the door jamb of the kitchen. “Ciao, carina, bueno serra. How are you?” he asked, smiling. I looked up, acknowledging his presence. “Ah, you’ve eaten already, bene,” he added, glancing at my sore attempt at a meal. His brow furrowed and he came over to me, hands on his hips. “Hey, what is it? Hm? Di mi, carina.”

Tell me.

What should I tell him? I knew he was exhausted, and frankly, so was I. Exhausted by life itself. “It’s nothing. Would you like something to eat?” I asked. He had already begun munching the sandwich remnant. He waved the hand that wasn’t guiding the sandwich to his face. “No, don’t trouble yourself. It’s alright.” He finished the sandwich, wiped the oil from his fingers, and with one last furtive glance at me, went back into the kitchen. He came back with two glasses and a bottle of wine.

“In vino veritas,” he said, opening the bottle and pouring us two generous glasses. “Now, tell me: what’s troubling you?” He was relaxed, his body positioned openly toward me. He wanted to hear.

“What can I tell you, Leo? I’m struggling with this, like I have been since we arrived here,” I replied, focusing on an imperfection in the wood of the table.

“Why are you struggling? Are you unhappy?” He was looking at me, waiting for me to make eye contact. I didn’t.

“I don’t know that its a matter of happiness, really. I just feel lost, unmoored. Like the last ship in open waters.”

“What can I do?”

I looked at him. He was quite serious.

“I don’t know.”

He sighed. “Lillya, you’re alone a lot, I recognize that. And I wish I could be with you more. But this is our life now. We wanted this life, you agreed to this life. Isn’t there something that you can find for yourself?”

“How, Leo? I don’t speak Italian well enough, your mother points that out daily. Your family still treats me like a stranger—“

“My family is waiting for you to feel like you are part of them. They are ready to have you any time you are ready to have them.” He lowered the volume of his voice. “This is all in your head, carina. Nobody wishes you anything else other than to feel at home here.”

“Your mother wishes you had left me in Portland.”

“She wishes no such thing. Such nonsense.”

I rolled my eyes. “I don’t use the right dishes, I don’t understand her ways, I can’t cook, I don’t sleep in the afternoons, my Italian incompetency is an abomination. I offend her, and she’s always around, so there is never a time where I feel like something I do might be right. And you don’t see it because she is your mother and she is in charge, without question.” My eyes were blazing as I looked at him. He sat back in his chair.

“My mother loves you as if you were her own daughter. She gets upset with herself for failing at her part of the communication—”

“Bullshit she does.”

“Let me finish. She was saying that, if only she could recall her English a little faster, she would be able to make the most beautiful lunch with you. Those were her words today.”

I shook my head and looked away. He leaned forward in his chair.

“I don’t know what to tell you, Lille. What do you want? You don’t know. Do you want me to marry you? Would that make you feel like you belong then? Do you want to be my wife? Italian by marriage, eh. Hm?” Again, he was serious.

“I don’t need you to marry me, Leo.”

“It’s not a matter of need, carina, it is a matter of what you want. Find that, and you will find peace.”

With that, he got up, took his glass and went outside, pulling the newspaper from under my magazine on the coffee table on his way.

Moments later, I joined him. He put the paper down.

I took a deep breath. “I don’t have a family that supports me like you do. Never have,” I said quietly. “You are right about me, you know. I have no idea what I want, or what moves me. I don’t think I’ve ever known.”

My family history was a story quite on its own. My parents were older when they conceived me, and my mother often told me that she had considered “a quick procedure” to take care of the “situation”. She was a career woman partnered with a man who loved work as much as she did. She doubted heavily that there was room for me in their lives. But, my father wanted me more than anything else, and as soon as they found out they were having a daughter, he refused to let her speak of anything but their future as a trio. That was the first step down a long path of resentment for my mother.

The second came with my name. Lillya. An uncommon, if not unheard of, girl’s name. My father loved the name ever since he had read it a novel about the Russian revolution. He loved history. My mother, on the other hand, was one of those Americans who thought history had no business being taken seriously in modern times. Much to her chagrin, the nurse scribbled down Lillya on my birth certificate, and they left it at that. No second name to mitigate the first. Instead, she chose to remind me at every opportunity that I was the greatest battle she ever lost. And she did lose. She lost my father, who died of heart disease when I was five. And she lost me slowly thereafter.

I tried to love her. She was my mother, after all. But the wounds she inflicted with her cruel words never had the chance to heal. Even after I had moved out of her house, had accomplished years of higher education, had been successful in every job I had ever set out to take, she still never saw me as anything but the embodiment of the worst possible situation. When Leo had met me, my father’s sister had taken me in and given me shelter from the last devastating meeting I had with my mother. We hadn’t spoken since.

“Lille,” he said, bringing me back to the present, “my family is your family. Whatever you decide to do, we are all behind you, amore.” He gave my hands an affectionate squeeze. “I need to see that sparkle in your eyes. I haven’t seen that since the first time I took you down to the seaside. But I know it’s there, in here—“ He placed his hand on my sternum, “—somewhere. Let it out, carina, and you will be at home anywhere you go.” He kissed my forehead and I reveled in the fact that he loved me enough to put up with the confused, lost, head case that I was. If only I could change all of that.

But I could. And I would.

When he came home the next night, I was covered in flour but had managed to make homemade ravioli with the help and patience of his sister, who spoke more English than she cared to let on in front of the rest of her family. I had also ventured down to the morning market to pick up some bread, fresh fish, and a few in-season vegetables that I sauteed in plenty of butter. I was, admittedly, somewhat drunk, but my spirits were higher than they had been in days, weeks even, and when he hugged me I knew that he was both surprised and happy to have found me using my time productively. And it felt good. Very good.

After dinner, I switched on the radio, and I practiced my Italian by singing to the lyrics I was sure of while Leo and I washed up the dishes. Ever the entertainer, he joined in, making up the words as he went and causing me to laugh until my full stomach began to hurt. After that, we made love on the couch after a shot of Limoncello, and went to bed.

Again I lay awake with my thoughts. Maybe if I spent less time at the harbor, alone and contemplating my failures, I would be able to immerse myself in something that could ignite my soul again. The question was: had it ever been ignited previously? I couldn’t say.

The Last Ship (pt. 2)

Leo knows his mind until his mother comes into view. Then, he only pretends he’s standing on principle. I watched these interactions with a certain level of bemusement, but mostly I wondered at him in utter confusion. For being one of the most confident, decided men I had ever met, Mama Sonia made quick work of him. Because if she wanted him to have more sauce on his pasta, the ladle would hover over his dish, they would banter for a few seconds, and then the contents would be spread over the plate, and that would be that. Not that I had any room to criticize; I let her do whatever she wanted with my food and otherwise. I already knew I was no match for her strong will and fiery spirit, so I did not ever choose to put up any resistance. Leo, though, did resist as if to further give her what she wanted, as if that was an integral part of the interaction. Somewhere in all of this, the myth (or was it?) of Italian men being mama’s boys sprang to the front of my mind. Even if it was true, though, what was I going to do about it? She was a constant figure in our lives now. We weren’t a million miles away on the coast of the Pacific Northwest; we were on the southern mediterranean coast of the Italian peninsula. These two were juxtapositions; like the smooth squid and the spiny urchins that the sun-weathered men fished from the sea and laid side by side at the market. Nevertheless, I would have to reconcile with the fact that he was no longer exactly the same man I had met and come to know in Portland.

My acceptance of this fact happened slowly. But, I learned quickly that nothing is accomplished or happens rapidly in the small seaside towns of southern Italy. The heat mixed with the heavy sea salted air does something to the brain, making it lackadaisical until around ten in the evening. Suddenly, at that time, front doors begin to open, restaurants fill up, and the piazzas are boasting plenty of life.

One night in August, a few months after we had arrived, there was a festival for one of the many patron saints. Seemingly the whole town followed the procession of the statue, walking behind the wheeled cart through the streets and down to the quay. Being a devout Catholic was to stand on ceremony; more strongly felt was the presence of Grappa and homemade spirits than the blessing of some pertinent yet stoic saint.

Southern Italians Live for The Night; that’s what I decided to name my memoir, should I ever establish the gumption to write one. For me, being out late was like discovering a whole new universe that I hadn’t actually ever realized existed to such a caliber. I had never been a late-night venturer. I much preferred quiet evenings at home to a long night of bar hopping or anything resembling an outing that dare cross into the wee hours of the next morning. Sleep and I shared a symbiotic relationship, and that was one partnership I was perfectly satisfied with. Of course, along came Leo with his tendencies to throw dinner parties where the meal itself lasted four hours at minimum, and a night out would easily lead to making friends with the owner of whatever restaurant or bar we found ourselves in, who then allowed us to stay for another round or two in the spirit of great conversation.

In the beginning, like in every new relationship, I was energized enough by my interest in and pursuit of the man himself. After awhile, though, my yawns became more and more indiscreet until I began limiting myself to the number of outings I partook in. Leo, God bless him, found no fault in that; he would go with friends and they would do exactly what they had always done while I stayed home in the company of a book or some other form of media.

But not here. My reclusive evening tendencies simply wouldn’t fly; if one wanted to have any manner of social life at all in southern Italy, one did not stay at home every evening. The afternoon nap was just as necessary to sleep off the effects of an indulgent meal as it was to stave off any unwanted tiredness come nighttime. Nights were for perusing the streets and enjoying society on display. Shops were open late. It was the inverse of the rest of the world, but that was the Mediterranean way.

So, when Leo pulled me up from the couch, wearing a fresh shirt and a pair of cotton pants, I went into the bathroom to freshen my face, add a little color to my lips, and then out we headed. Sometimes we would be in the company of some members of his impossibly large family, and sometimes we would stroll along, hand in hand or arm in arm, just the two of us. In those moments, a little drunk on whatever we had had a few glasses of, I knew that, as long as I could feel his body next to mine, I could make it here.

When Scars Become Art

Perception is an interesting thing. Particularly when it comes to body image: How I’ve seen myself for the last three years, for example, turns out to be completely different than the image other people have been observing. That’s not all that uncommon. In fact, it’s probably rather normal. I know that I critique myself much harder than anybody else would critique me. But, I also know that the perception one has of oneself can be incredibly strong; strong enough that I believed it to be the only truth.

Perception is an interesting thing. Particularly when it comes to body image: How I’ve seen myself for the last three years, for example, turns out to be completely different than the image other people have been observing. That’s not all that uncommon. In fact, it’s probably rather normal. I know that I critique myself much harder than anybody else would critique me. But, I also know that the perception one has of oneself can be incredibly strong; strong enough that I believed it to be the only truth.

Until recently, I would not have even considered showing my belly area to the light of day; not even for one second. Like many women who have carried a child, the skin in that particular area has undergone some serious changes; changes that I had viewed as absolute unsightly destruction. In fact, I would cringe anyone happened to catch sight of what was underneath my shirt.

Viewing myself in a confident and positive way happened only just recently. It was a process that took quite a long time. I had to dismantle the image I had built of myself to allow the new idea some time and space to grow and replace it. There were several outside factors to all this, but what it came down to, I realized, is that wearing anything–be it a bold outfit or a patchwork of scars–with confidence is going to make all the difference for the image I maintain of myself, and also how others perceive me. Frankly, I never (and when I say ‘never’, I truly mean it) thought I would be wearing an outfit that brazenly shows off my imperfections, let alone posting the photos thereof to a public space online. Yet, here we are.

I know that a lot of men and women alike struggle with body image in some ways or others. And a lot of us suffer silently. For me, it took a long time to believe that the changes undergone by my body were not things to be dismayed or disturbed by; rather, they show a part of my story: The reality that I carried a child, and the metaphor of the scars that were left as a remnant of the events of my past. In both of these instances, I would not be the woman I am today without them. So, like in any situation that depends on choice of attitude, I’ll choose to wear the scars with pride, confidence, and a smile. And I’ll continue to feel comfortable in my own skin. After all, everyone has scars; some are just more visible than others.

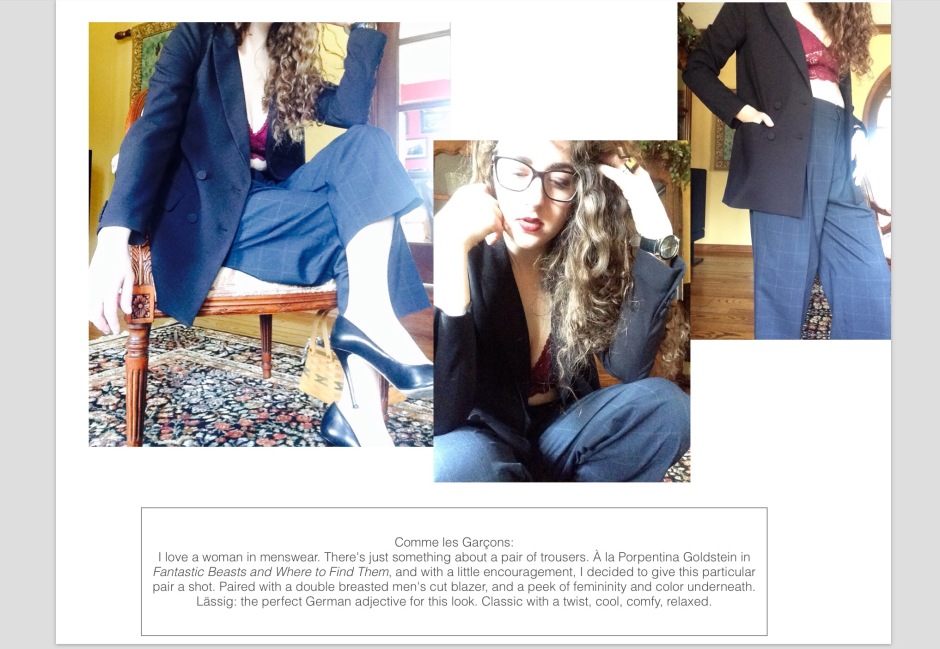

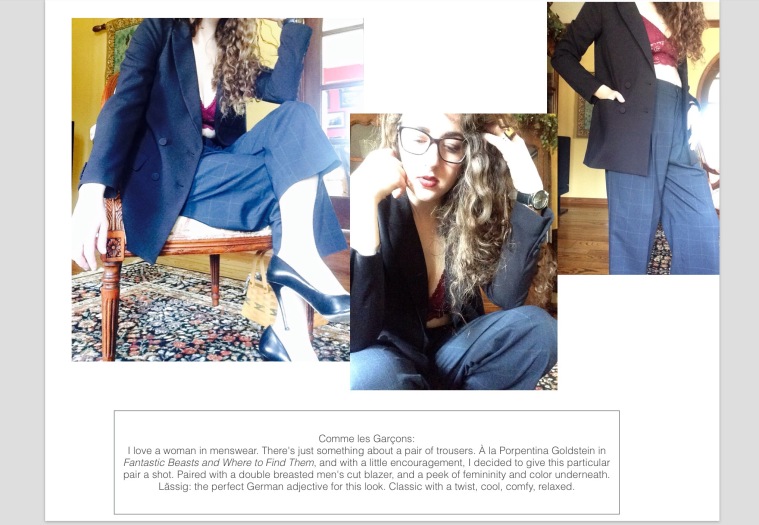

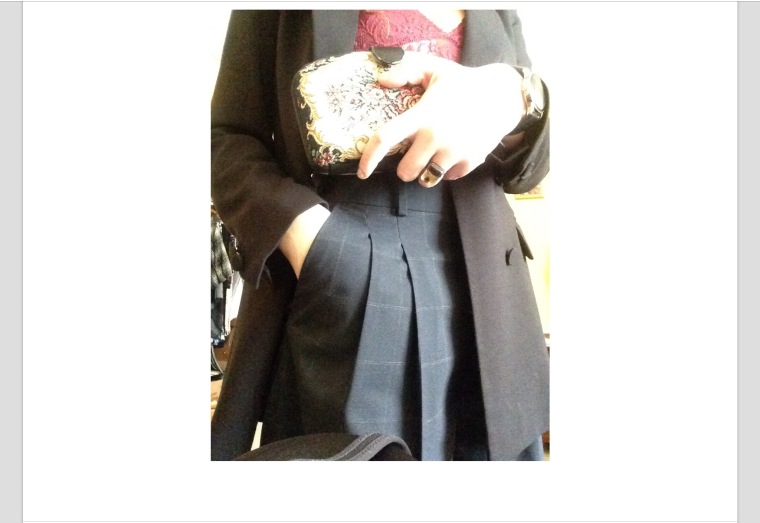

Comme les Garçons

When You’re Ready to Wake Up, You Will

It’s a simple metaphor really; waking up from a restful sleep when the body is ready.

The truth of it, though, is that I need to wake up from so much more than sleep sometimes. I find myself in situations that I desperately need to come to some realizations about so I can open my eyes to what life and the universe is trying to tell me.

I think the best example of this is a relationship I was in for several months. It was unexpected -a truly pleasant surprise- and we had everything we could ask for in the beginning; fun, peace, potential. He was interesting and inspiring, extremely intelligent and sharp-witted. Conversation came easy and was always enjoyable and stimulating. We related well to each other and I even found that he challenged me in positive ways. As time went on, I felt myself being moved to do things for myself that I hadn’t realized were possible previously. He awoke in me both potential as well as actions that had been dormant for too long. Additionally, the amount of respect we had for each other was the oxygen to my life’s blood; it was incredible.

But, after awhile, I began to realize that he and I were two brilliant souls who didn’t share the same energy. It went beyond having different priorities, philosophies, and mindsets; I believe a partnership can work in spite of those things. No, it was not any of that. Though we still had peace and respect in our relationship and it was a pleasure to spend time with him, it was also the truth that we were both searching for something that the other would not be able to give. We both knew what we had in the other; it wasn’t that we weren’t good enough. It was that we were not in alignment. And we never would be. But this was not a fault of either of ours; it was just a fact of the universe.

At times, when I was really honest with myself, I could feel the small jolts pulse through me that acknowledged this fact. Apart from the subtle things that his body language revealed, in addition to the words he chose to express, there were also subtle signs from random places in the universe that were all gentle prods for me to break the slumber and face the day. This is where it became paramount for me to wake up. Because I think he knew it before I did. Yet he was patient enough for me to come around to it, too. And, in my own time, I did. I woke up.

Something amazing I find about life is that events or people come, they make an impact, and then things move on. The crucial moment is realizing when to let them go. In this case, he came into my life to show me some really powerful things about myself; things that, without our chance meeting, I maybe wouldn’t have realized, or they would’ve taken me much longer to realize. He was a catalyst for change in me, and together we did great things. But letting him go was also a great feat because, had I held on to him, peace would’ve turned to misery, and all the positives would’ve unraveled to become something neither of us would’ve enjoyed any longer.

Every day is full of chance meetings. Being open and receptive to them is something I have come to enjoy immensely. I’ve had conversations with strangers at tables across from mine at restaurants or in the line at a store, and they sometimes end up being the most uplifting minutes of the day. The fluidity of the exchange between humans can be the most beautiful happenings. For that same reason, letting go can be incredibly difficult, seemingly impossible at times. However, when you are ready to wake up, you will.

Then, greet the morning with a “good day”; and a good day it will be, indeed.

Between Us

Rhythm. The sound of the heart beating life through the body.

Rushing. The blood pushes through the veins and vessels.

Reaction. The body functions as it is meant to.

Silence. The moments in which the inner workings of the body are the most pronounced; every nuance can be felt at a magnitude that is otherwise impossible to detect. The silence speaks in this way; it speaks as the heart pumps, as the blood rushes, and as the organs and systems function without strain. This is peace. These are moments when the soul speaks to the body; tells it truths that otherwise are unable to be heard. Perfect stillness allows for all encompassing realization and acceptance. There are things to be heard, if only one finds the right moment to listen.

I haven’t known peace for years. No, I was used to the utter turmoil that every moment had the potential to become. Every molecule in my body was set afire, threatened to be burned asunder by the disrupting battles that seemed to take place without pause. Negative sensory overload does not bide with peace or understanding. It only knows upheaval and chaos.

What happens when the moment for peace finally does come? What is to follow?

A quiet unlike I have ever known. The opportunity to just be; to exist without any force pulling in any one direction. The body performs, the soul is free, the mind is calm and uncluttered. The energy is free to move through clear space, passing smoothly from his skin to mine.

I have come to know that people say many things; things they mean in all earnest but can never deliver on, things they say to be soothing or reassuring but without any truth behind them, and things that were meant in the moment but were forgotten shortly thereafter. They say many things, but I have learned to allow intuition to guide me based on what they do; how they perform, what their energy says to me, what their eyes are revealing, and how the silence between us feels.

Words are powerful; but there is nothing more honest than the moments of quiet discovery where silence says what words cannot. And I listen with my whole body in these moments. They tell me everything I need to know.

It is one thing to accept another person’s flaws or past. Of course these things are inevitable and are often the stones upon which our lives have been built, brick by brick, turning us into the individuals we are and are trying to become. In that way, they are important to be acknowledged.

But, it is another thing entirely when they are acknowledged, and yet are not given the weight of importance that they previously had been given. When they are reduced to merely the stones, rather than the foundation, there is freedom. When scars become just another feature of the skin, when true and terrible stories become memories without power, when there is congruent honesty in both words and movements, so then is there the great and insurmountable presence of peace between us. It comes without ceremony or announcement of its arrival; it comes merely as a gentle sigh, a small alignment of two bodies, a space in which there are no further needs or desires than to just be free to passively celebrate the equilibrium of the moment.